A bear in wolf’s clothing: Insights into the infrastructure used by Anonymous Sudan to attack Australian organisations

Published by CyberCX Intelligence on 19 June

In March and April 2023, a threat actor calling itself Anonymous Sudan claimed to have conducted at least 24 distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks on Australian organisations in the aviation, healthcare and education sectors. CyberCX Intelligence observed and investigated several of these attacks. Our findings indicate that Anonymous Sudan is unlikely to be an authentic hacktivist actor, as it claims, and instead may be affiliated with the Russian state.

Key Points

- On 25 and 31 March 2023, CyberCX observed high-traffic Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks against Australian organisations. The attacks were threatened in advance and claimed after the fact by a purported hacktivist threat actor, Anonymous Sudan.

- CyberCX assesses that Anonymous Sudan is unlikely to be an authentic hacktivist organisation. This assessment is based on a range of tradecraft observations, including Anonymous Sudan’s sustained, routine use of paid infrastructure, which is likely to have substantial cost.

- CyberCX assesses that there is a real chance that Anonymous Sudan is affiliated with the Russian state.

- Anonymous Sudan is publicly aligned with other pro-Russia threat actors that are likely affiliated with the Russian state.

- While the motivation for a nation-state to support DDoS attacks against private organisations is unclear on an incident-by-incident basis, persistent low-level disruption of Western countries is consistent with established Russian information warfare strategies.

- CyberCX assesses that Anonymous Sudan is likely to increase its tempo of operations over at least the next three months.

BACKGROUND

Anonymous Sudan

Origins and identity

- Anonymous Sudan commenced operations via Telegram in January 2023, adopting the ‘Anonymous Sudan’ moniker in reference to a 2019 operation by Anonymous, a loose hacking collective.

- However, CyberCX assesses with high confidence that Anonymous Sudan is unlikely to be an authentic hacktivist organisation and that Anonymous Sudan is unlikely to be geographically linked to Sudan.

- Anonymous Sudan has no known overlap with the original membership of the 2019 Anonymous Sudan operation, which was anti-Russia and pro-Ukraine.[1]

- In February, Anonymous Sudan was denounced by a prominent Anonymous account as not being a part of the Anonymous collective.[2]

- Anonymous Sudan primarily posts in English and Russian. Increasingly, Anonymous Sudan posts in Arabic and makes cultural and nationalistic references to Sudan. However, Anonymous Sudan’s first post in Arabic was more than a month after its creation, and after security researchers had begun to question its ideological affiliations.

- Anonymous Sudan’s operations are consistent with the UTC-3 time zone, which covers East Africa including most of Sudan but also eastern Europe including Moscow.

Operations

- CyberCX assess that Anonymous Sudan is likely to be an individual or a small, coordinated group rather than a grassroots hacktivist organisation.

- Anonymous Sudan operates with a level of coordination unusual for a collective of issue-motivated hacktivists.

- Most authentic grassroots hacktivist organisations observed by CyberCX plan activities in an at least semi-public way, discussing targeting and coordinating operations in forums and group chats. Anonymous Sudan declares specific targets as it attacks, implying it is a closely held operation.

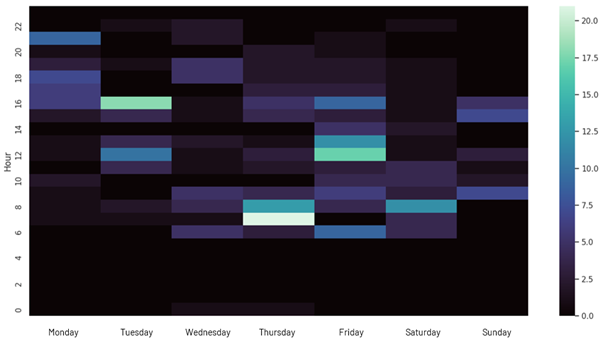

- Anonymous Sudan operates with a level of consistent scheduling unusual for a collective of issue-motivated hacktivists.

- We have observed no Anonymous Sudan attacks claimed between UTC 22:00 and UTC 06:00. More than 80% of claimed attacks fall between UTC 6:00 and UTC 18:00.

Figure 1 – Anonymous Sudan’s pattern of life (UTC) by number of publicly claimed DDoS attacks per hour.

The pro-Russian ‘hacktivist’ threat actor ecosystem

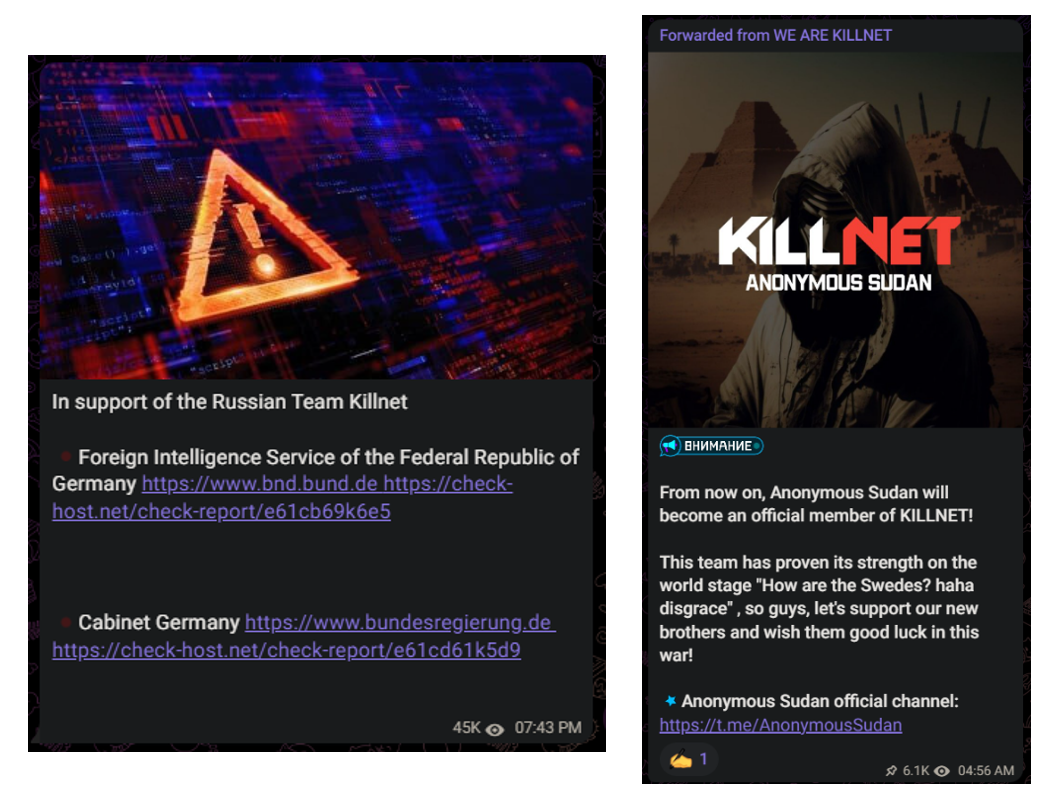

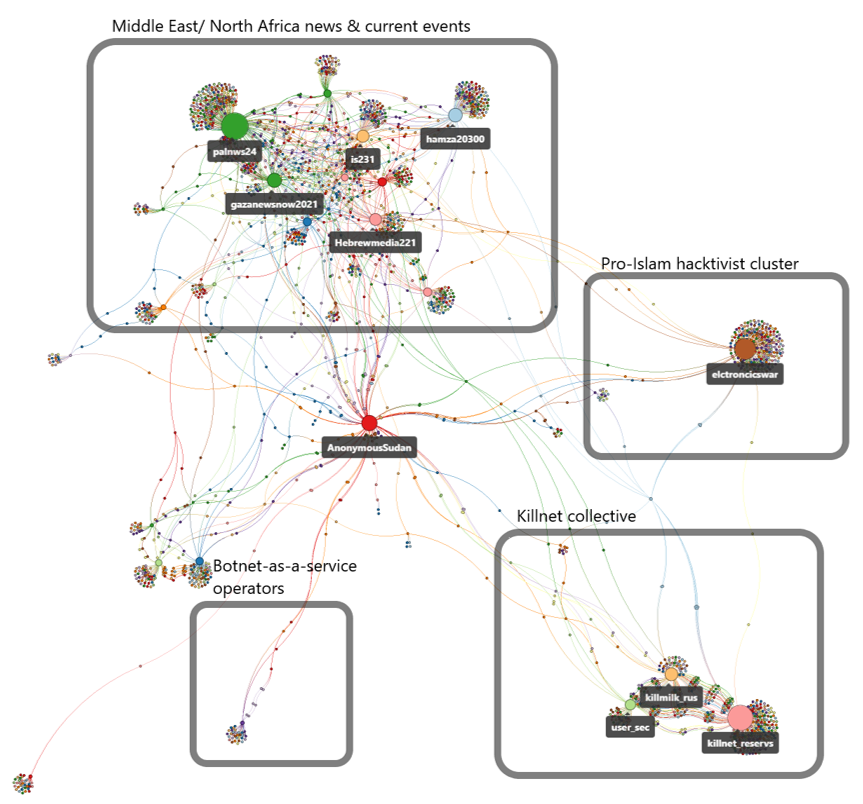

- Anonymous Sudan is publicly pro-Russia and a member of the pro-Russia hacktivist collective, Killnet. Anonymous Sudan and pro-Russia hacktivists, including the primary Killnet Telegram channel and Anonymous Russia Telegram channel frequently cross-promote attacks.

Figure 2– Anonymous Sudan’s first show of support for Killnet on 25 January (left) and announcement of joining Killnet on 20 February (right), both translated from Russian.

Figure 3 – Anonymous Sudan’s relationships with other Telegram personas by channel forwards and tags.

- Both the number of pro-Russia ‘hacktivist’ personas, and their tempo of operations, expanded significantly following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. By 2023, most of this activity was undertaken by members of the Killnet collective (which includes Anonymous Russia and Anonymous Sudan), [3] centred around the primary Killnet account, @killnet_reservs.

- In June, Killnet-affiliated threat actors including Anonymous Sudan announced plans to launch non-DDoS attacks on Western financial institutions and the SWIFT network in conjunction with REvil. REvil is a formerly prominent Russia-based cyber extortion group linked to the cyber extortion attack against Medibank in October 2022.

- CyberCX notes that previously known REvil communications channels have not corroborated a partnership with Killnet or Anonymous Sudan. REvil’s darknet sites have been offline for at least the last four months.

Russian intelligence’s links to ‘hacktivist’ personas

- It is almost certain that Russian intelligence is affiliated with or operates through pro-Russia hacktivist personas. We assess that it is highly likely that at least some members of the Killnet collective are linked to the Russian state.

- In April 2023, leaked US signals intelligence reportedly linked the pro-Russian hacktivist actor and Killnet member Zarya to an intrusion against a Canadian gas pipeline.[4] The intelligence reportedly states that Zarya was on standby for instructions from the FSB, which “anticipated that a successful operation would cause an explosion”.[5]

- In April 2023, the Ukrainian Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-UA) linked a cyber attack against a Ukrainian government organisation to the GRU. CERT-UA identified that the attack plan, including both a destructive script and target IP address, had been posted in the Telegram channel of pro-Russia hacktivist, CyberArmyofRussia_Reborn before the attack.[6]

- In September 2022, security researchers identified coordination between pro-Russia hacktivists XakNet, Infoccentr and CyberArmyofRussia_Reborn and GRU cyber operations. The pro-Russia hacktivist groups leaked information stolen during GRU wiper attacks within 24 hours of intrusions.[7]

- Most pro-Russian hacktivist activity, including Anonymous Sudan’s, involves DDoS attempts, which if successful are comparatively low-impact. We assess that the objectives of pro-Russian hacktivist actors are highly likely informational, [8] and may include:

- Exaggerating the success of their attacks to create public chaos and uncertainty.

- Drawing attention to pro-Russian narratives and propaganda.

- Creating a vehicle to amplify Russian disinformation.

- Distracting and driving cost into Western cyber defence.

Hacktivism as a smokescreen for Russian interests

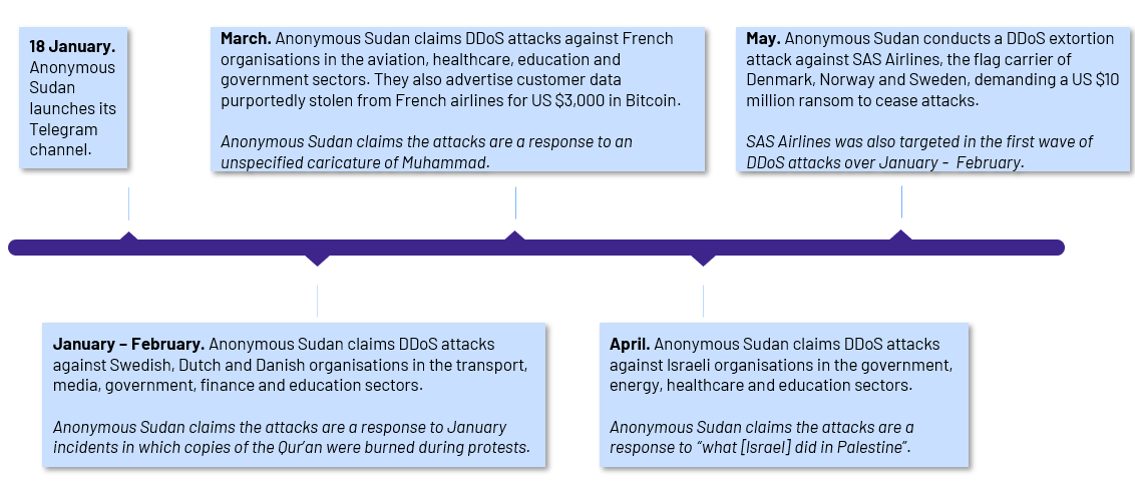

- Anonymous Sudan primarily targets Western organisations in the government, media, healthcare and transport sectors.

- Anonymous Sudan claims to target countries in response to anti-Islamic action or sentiment, but also periodically attempts to monetise its activities.

Figure 4 – Select targets of Anonymous Sudan (excluding Australia).

- CyberCX notes Russian’s longstanding use of religious-related disinformation to polarise Western societies, for example by stoking Islamophobic sentiment.

- CyberCX also notes that a Qur’an burning in Stockholm in January was linked to a former contributor to Kremlin-backed media outlet, Russia Today.[9] Anonymous Sudan was created three days prior to the Stockholm Qur’an burning. It then commenced DDoS operations against Swedish, Dutch and Danish organisations, purportedly in response to this activity.

Attacks on Australian organisations

- Between 24 March and 1 April, Anonymous Sudan claimed to have conducted DDoS attacks on at least 24 Australian organisations in the aviation, healthcare and education sectors.

- Anonymous Sudan joined a broader hacktivist campaign against Australia, dubbed “opAustralia”, which CyberCX has moderate confidence had authentic religious motivations.

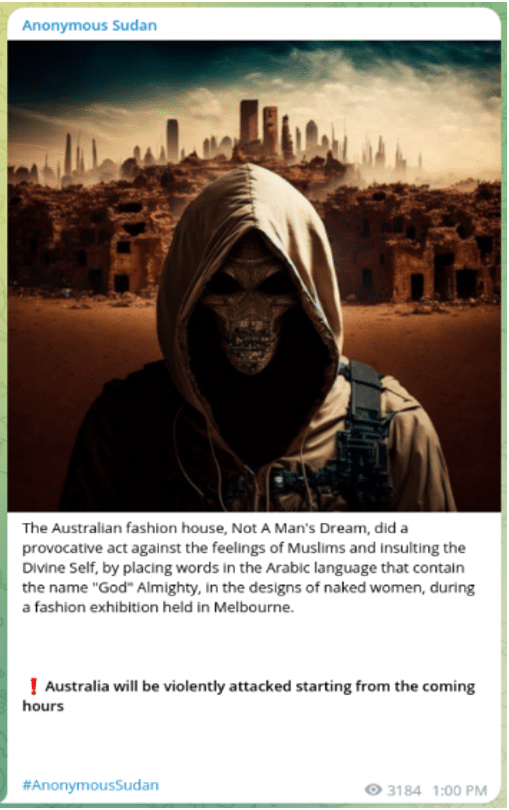

- The “opAustralia” campaign was initiated on 17 March by a purportedly Pakistani hacktivist group. The campaign was claimed as a response to clothing bearing the Arabic text “God walks with me” being displayed at the Melbourne Fashion Festival. The use of the Arabic ‘Allah’ (meaning God) prompted criticism based on the context in which it was used.

- Hacktivist groups other than Anonymous Sudan claimed to have targeted at least 80 Australian organisations with DDoS attacks prior to Anonymous Sudan joining the campaign on 24 March.

Figure 5 – Anonymous Sudan’s initial threat to target Australia, posted to its Telegram channel on 24 March.

Attack infrastructure

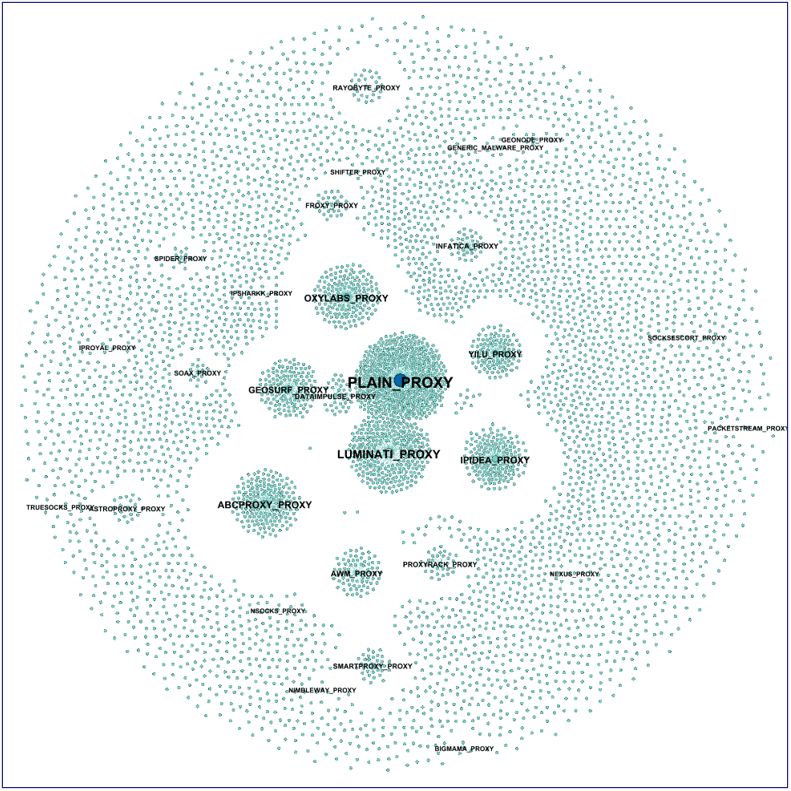

- CyberCX observed a significant overlap in Anonymous Sudan’s DDoS tactics and infrastructure used in attacks on Australian organisations on 25 and 31 March. Anonymous Sudan used proxies to distribute and conceal the origin of DDoS traffic.

- We assess with high confidence that Anonymous Sudan’s proxy infrastructure was substantially composed of paid proxy services.

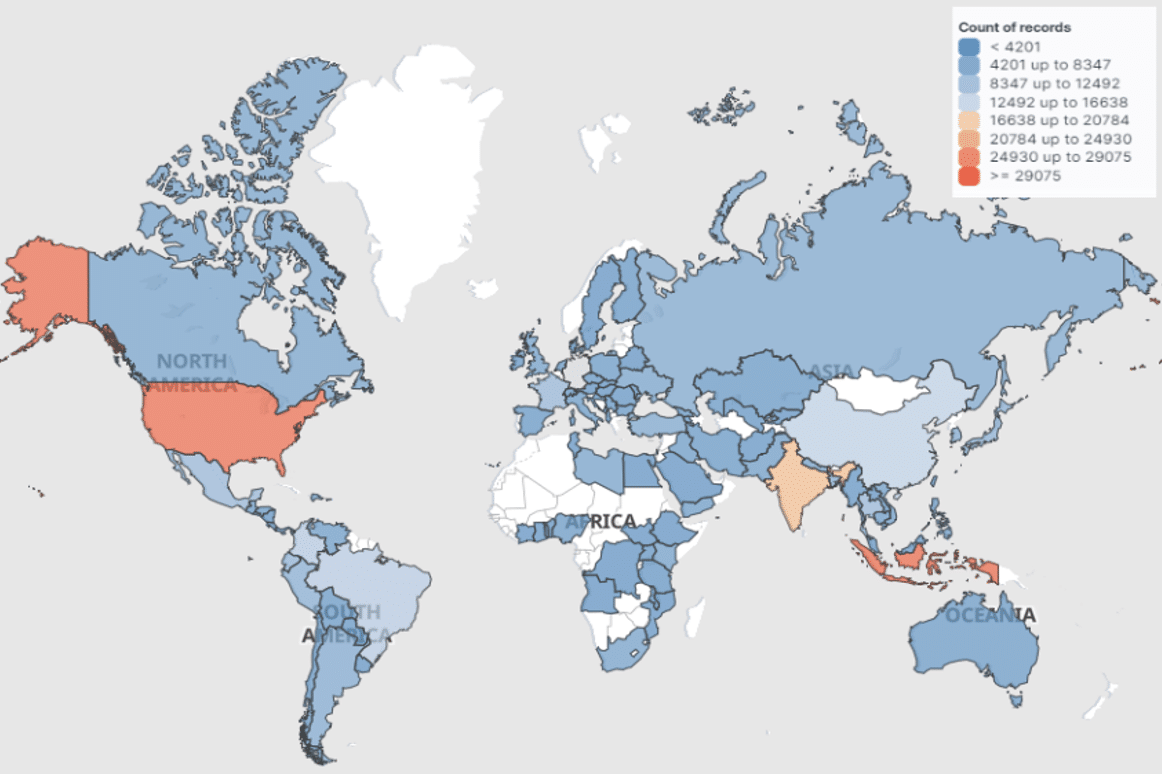

- The DDoS attacks focused on application layer HTTP(s) flooding. Request headers and arguments were randomised in distinct patterns across HTTP floods, suggesting coordination between traffic sources. Traffic was highly dispersed, with the common infrastructure across attacks spanning 1720 Autonomous Systems (AS) over 132 countries. Indonesia was the most represented country of origin, followed by Malaysia and the United States.

Figure 6 – Anonymous Sudan DDoS traffic sources by country of origin.

- Anonymous Sudan had a low reliance on TOR for traffic dispersal. Around 2% of the common infrastructure was composed of likely TOR exit nodes, contributing at least 4% of the overall attack traffic volume.

- Approximately 6% of the common infrastructure was composed of known “open” proxies, which are proxies that forward traffic for any user without authentication. Open proxies generated at least 10% of the overall attack traffic volume.

- Approximately 27% of the overall attack infrastructure related to likely paid proxy networks, accounting for at least 33% of the overall attack traffic volume.

- The largest paid proxy network traffic contributor was Plain Proxies (also known as Data Impulse Proxies), which contributed approximately 6% of the overall traffic volume from 8% of the unique infrastructure.

- Bright Data (also known as the Luminati proxy) and the IPIdea proxy were also major traffic sources, each contributing approximately 5% of the total traffic from approximately 5% of the total infrastructure.

Figure 7 – Anonymous Sudan DDoS traffic sources by connection to known proxy networks.

Note that IP addresses may be shared between multiple proxy providers and inclusion does not necessarily imply service abuse.

- We assess that it is almost certain that the proportion of overall infrastructure that related to paid proxy services is higher than the 27% identified. A core element of paid proxy services’ value proposition is that proxies are difficult to identify and track.

- Proxy services, including the services likely to have been used by Anonymous Sudan, routinely advertise based on low detection rates and control of IP addresses in residential IP space.

- Anonymous Sudan’s use of proxies implies that DDoS traffic was generated from an upstream source. We assess that there is a real chance that Anonymous Sudan used paid cloud infrastructure for upstream traffic generation. Paid cloud infrastructure provides a DDoS threat actor with access to scalable and high-performance infrastructure but poses additional infrastructure costs.

- In February, security company Truesec identified that Anonymous Sudan used 61 IBM/SoftLayer servers to generate traffic during DDoS attacks against Swedish organisations in January. [10] During the same attacks, Anonymous Sudan used proxies to distribute traffic and conceal its origins, consistent with our observations of attacks against Australian organisations.

Infrastructure costs

- Given the likely use of paid infrastructure since January 2023, Anonymous Sudan has plausibly expended tens of thousands of dollars to sustain its DDoS operations. We assess that substantial use of paid infrastructure is highly suspect for any ideologically motivated group. Anonymous Sudan’s likely infrastructure costs are particularly suspect for a group claiming to originate from Sudan, a nation with a well-below global estimated average household income of US $460 per year.[11]

- We assess that it is highly likely that Anonymous Sudan paid for proxy services rather than abusing free trials or breached accounts. We observed consistent, very high capitalisation of the same paid proxies in attacks separated by six days, indicating stable procurement and consistent control or access by Anonymous Sudan.

- We assess that proxy network operators are frequently targeted for service abuse and are likely to be hardened against fraudulent account creation and account takeovers, particularly at industrial traffic scales.

- Given the opaque nature of paid proxy networks and the highly varied pricing of cloud services, it is difficult to estimate Anonymous Sudan’s likely expenditure on infrastructure.

- Based on the identifiable aspects of proxy infrastructure we observed, we assess that Anonymous Sudan’s proxy infrastructure is likely to cost at least AU $4000 per month of usage.

- Anonymous Sudan’s upstream traffic generation infrastructure is likely to require substantial computing power and network bandwidth to saturate the proxy infrastructure. We assess that it is plausible that Anonymous Sudan’s traffic generation infrastructure also costs thousands of dollars per month.

- Open source reporting indicates that 35% of internet traffic to Australian aviation organisations was DDoS traffic while Anonymous Sudan’s attack was underway.[12] The same reporting indicates that 40% of internet traffic to Australian education institutions was DDoS traffic while Anonymous Sudan’s attack was underway.

- Anonymous Sudan describes its DDoS capability as consisting of 35 million requests per second at the application layer and 4 Terabytes per second UDP or 1.7 Terabytes per second TCP-SYN at the transport layer.

- In early June, Anonymous Sudan promoted a DDoS-for-hire service, Skynet. Anonymous Sudan stated that it had tested Skynet. Skynet advertises that it uses high-powered cloud servers for traffic generation and purports to have an application-layer DDoS capability of 500 million requests per second.[13] Skynet’s price for its highest tier is US $14,000 per 30 days.

- While we are unable to assess the veracity of Anonymous Sudan or Skynet operators’ claims, the indicative price provides some insight into the possible cost scale for large application-layer DDoS infrastructure.

- Anonymous Sudan’s upstream traffic generation infrastructure is likely to require substantial computing power and network bandwidth to saturate the proxy infrastructure. We assess that it is plausible that Anonymous Sudan’s traffic generation infrastructure also costs thousands of dollars per month.

- Based on the identifiable aspects of proxy infrastructure we observed, we assess that Anonymous Sudan’s proxy infrastructure is likely to cost at least AU $4000 per month of usage.

Anonymous Sudan: Where next?

- We assess that Anonymous Sudan is almost certainly publicity motivated. For example, Anonymous Sudan monitors and distributes media reporting about attacks and tactics.

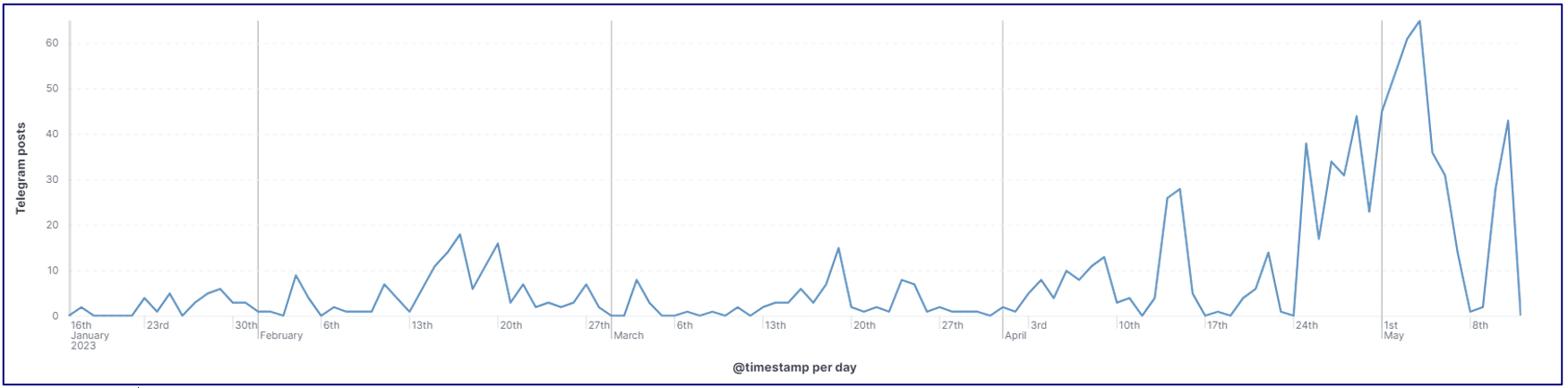

- Anonymous Sudan’s Telegram audience and engagement has increased significantly over time, a development we assess is likely to spur increased activity by Anonymous Sudan for at least the next three months.

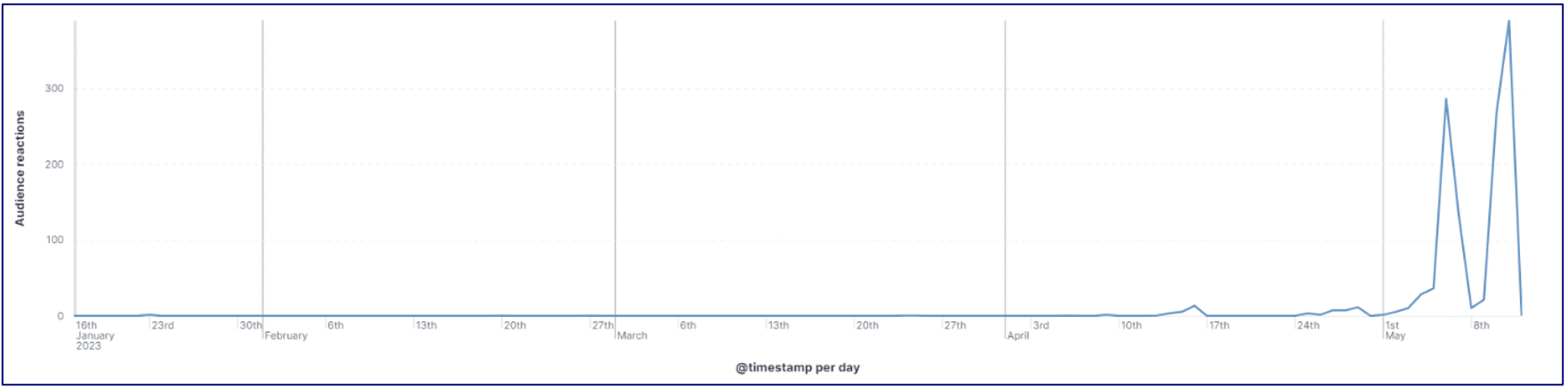

- Anonymous Sudan now has more than 60,000 followers on its Telegram channel and reactions to its posts dramatically increased through May.

Figure 8 – Anonymous Sudan’s activity over time by Telegram posts per day.

Figure 9 – Anonymous Sudan’s audience reaction over time by reactions to Telegram posts.

- While Anonymous Sudan superficially resembles other hacktivist DDoS actors, its apparent access to significant resources and its dubious ideological associations means that it poses an atypical threat.

- Anonymous Sudan’s resources and at least moderately sophisticated infrastructure management skills facilitate intense DDoS attacks that do not rely on amplification techniques or known malicious infrastructure that can be blocked in advance.

- CyberCX encourages organisations with critical public facing assets to ensure that their DDoS mitigation strategies account for the use of paid proxy services and are suited to mitigating application-layer attacks. DDoS solutions that do not adaptively block traffic are likely to perform poorly against Anonymous Sudan’s attacks.

- Organisations attacked by Anonymous Sudan should be aware that attacks are likely to have a direct financial cost to Anonymous Sudan.

- DDoS attacks are, in essence, a battle of resource expenditure between threat actors and targets. Threat actors typically rely on a combination of amplification techniques and compromised infrastructure (such as botnets) to maximise impact while minimising cost. Based on our observations, Anonymous Sudan has at most a limited reliance on these techniques, shifting the usual asymmetry back in network defenders’ favour. This dynamic presents a rare opportunity for network defenders to drive direct costs into Anonymous Sudan through efficient management of DDoS attacks.

[1] https://files.truesec.com/hubfs/Reports/Anonymous%20Sudan%20-%20Publish%201.2%20-%20a%20Truesec%20Report.pdf

[2] As above.

[3] https://go.recordedfuture.com/hubfs/reports/cta-2023-0223.pdf

[4] https://therecord.media/russia-hacktivist-threat-to-canadian-pipelines-a-call-to-action

[5] https://zetter.substack.com/p/leaked-pentagon-document-claims-russian

[6] https://cert.gov.ua/article/4501891

[7] https://www.mandiant.com/resources/blog/gru-rise-telegram-minions

[8] See also https://go.recordedfuture.com/hubfs/reports/cta-2023-0223.pdf

[9] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jan/27/burning-of-quran-in-stockholm-funded-by-journalist-with-kremlin-ties-sweden-nato-russia

[10] https://files.truesec.com/hubfs/Reports/Anonymous%20Sudan%20-%20Publish%201.2%20-%20a%20Truesec%20Report.pdf

[11] https://www.worlddata.info/country-comparison.php?country1=SSD&country2=USA

[12] https://blog.cloudflare.com/ddos-attacks-on-australian-universities/

[13] CyberCX notes that this claim is almost certainly highly inflated. The highest volume publicly reported application-layer DDoS attack occurred in February 2023 and peaked at 71 million requests per second. Attacks at this scale are likely to be rare, with the second highest volume attack occurring in June 2022 and peaking at 46 million requests.

Guide to CyberCX Cyber Intelligence reporting language

CyberCX Cyber Intelligence uses probability estimates and confidence indicators to enable readers to take appropriate action based on our intelligence and assessments.

| Probability estimates – reflect our estimate of the likelihood an event or development occurs | ||||||

| Remote chance | Highly unlikely | Unlikely | Real chance | Likely | Highly likely | Almost certain |

| Less than 5% | 5-20% | 20-40% | 40-55% | 55-80% | 80-95% | 95% or higher |

Note, if we are unable to fully assess the likelihood of an event (for example, where information does not exist or is low-quality) we may use language like “may be” or “suggest”.

| Confidence levels – reflect the validity and accuracy of our assessments | ||

| Low confidence | Moderate confidence | High confidence |

| Assessment based on information that is not from a trusted source and/or that our analysts are unable to corroborate. | Assessment based on credible information that is not sufficiently corroborated, or that could be interpreted in various ways. | Assessment based on high-quality information that our analysts can corroborate from multiple, different sources. |